Republics and Racism

Today's democracies, with their norms of liberal toleration, universal equality, and individual human rights, seem to stand in the starkest moral contrast to ancient Sparta. And yet there is a clear genealogical connection between modern, Western democracy and the classical republicanism of ancient Mediterranean states such as Sparta. Throughout the history of Western political thought, Sparta has in fact been one of the most celebrated of the ancient Greek republics. We might be tempted to say "second only to Athens," but according to many commentators, Sparta was plainly superior to Athens. It was praised in its own time by Athenians themselves, including Plato, who came close to calling it the ideal constitution. It was praised in the Roman republic for exemplifying "mixed government" and martial prowess. Sparta was lauded in the Renaissance by Niccolò Machiavelli for its stability and longevity. And during the Enlightenment, it was held up as a paragon of republican civic virtue by Jean Jacques Rousseau.

It seems strange indeed that our modern democracies should be so doctrinally opposed to one of the ancient governments that inspired them. Some critics of Western modernity might, however, find the genealogical connection to Sparta neither surprising nor something to be celebrated. Michael Hanchard's The Spectre of Race: How Discrimination Haunts Western Democracy suggests such a view. Are not the leading republics of the post-Enlightenment West founded on brutal conquest and perpetuated through slavery, genocide, racism, and xenophobic nationalism? The West has traditionally been very proud of its classical republican roots, even though Enlightenment liberals critiqued and revised certain elements, drawing a distinction between the problematic "liberty of the ancients" and the new and improved "liberty of the moderns." (Benjamin Constant, 1819). But should the West be proud of its republican roots? Consider the stains upon American democracy in particular: its history of slavery and later apartheid, Native displacement and genocide, racist immigration policies, 20th century imperialism, and even its own dalliances with eugenics. What if these things are not so many aberrant failures to live out the true meaning of our republicanism? What if they are a deep and abiding part of republicanism?

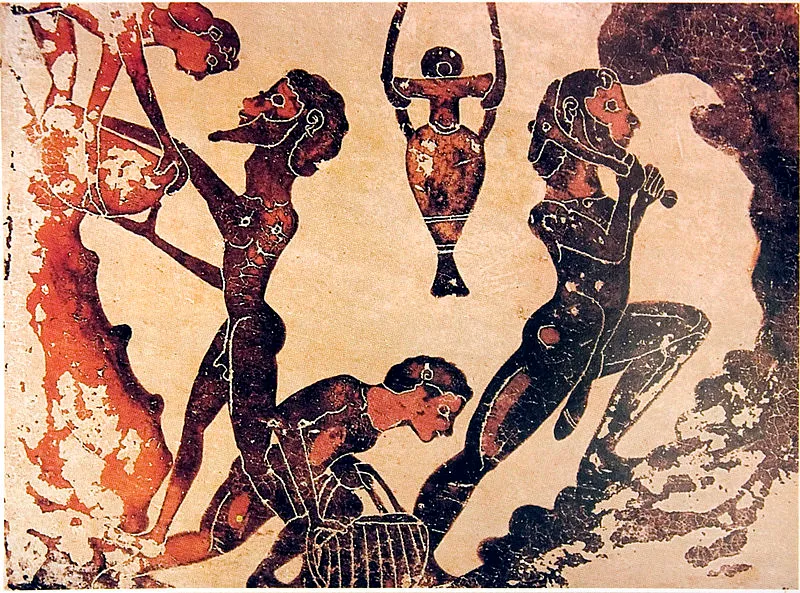

Michel Foucault found a link between the transition to Enlightenment politics and a new obsession with the hygiene, health, and purity of the race/nation. But there may be deeper historical patterns at work (as Agamben and others have argued). If we look for a pre-modern example of a society concerned with Foucaultian biopoltics, Sparta wouldn’t be a bad place to start. Rather than a peculiarly modern phenomenon, biopolitics may be a tendency inherent in republican governments generally. Modern republics often espouse universal humanistic values, but absent the global "republic of republics" envisioned by Immanuel Kant, all historical republics have been created by and for a specific people. In coming to rule itself, it seems a people feels a special need to define itself, to set exclusive bounds on citizenship, and to construct and police a particular identity.

Under monarchies, the aim of the state is primarily preserving the political power of the dynasty. Monarchies are held together by fear, raw power, and personal loyalty. This basic fact is probably the key to their relative weakness in relation to their size. They do not require, nor do they tend to propound an especially solidary political identity such as race or nation. This is why what we now regard as the diverse and distinct "nations" of Europe could be ruled, right up until the turn of the twentieth century, by monarchs who were cousins to one another. Under a functioning republic, on the other hand, the goal of the state is the wellbeing of a people; a people that has not only to be defined but also shored-up, consolidated, and bound together with strong ties. Without the center of gravity that a monarch provides, republics traditionally depended on a spirit of deep horizontal attachment and fraternity. In the modern context, we often call it nationalism. At its best, perhaps, it is patriotism and "civic virtue." At its worst, it becomes racism, xenophobia, and fascism.

Sparta was a fascist republic, and the troubling part is that its fascism was not necessarily in tension with its republicanism. Traditionally, "faction" was held to be the political disease peculiar to republics. The primary republican fear, in other words, was the fear of disunion and division. But equally to be dreaded is republican fascism. Fascism can destroy republics, transforming them into monarchic forms with sometimes remarkable rapidity, as with the Third Reich. Large republics may be especially prone to fascist collapse into monarchy, as the classical wisdom says small republics are easier to maintain internally. This may explain why fascism is seen as an anti-republican force in the modern age. But fascism does not always destroy its host. Fascist Sparta maintained institutions of power-sharing among the exclusive citizen class for many centuries. Low grade fascism--call it "white nationalism," "ascriptive Americanism" (Rogers Smith), "slow fascism" (Jairus Grove), or just plain racism--has persisted for years in the American republic. Fascism is a threat to republics, but is also a threat to our common humanity that can find shelter under popular rule.

Good points. Suggest we need an update on "Republic"--the City States born with that name were by nature monoethnic and monoreligius. In a sense the American Republic inherited some degree of ethnic and religious diversity not from their republican nature, but from the pragmatic requirements of ancient empires from Sargon, Gemgis Kahn, through Rome to grant religious freedom and 'ethnic custom freedom' (maybe there's a word fot that!) to their diverse inhabitants. I mean as long as you grant to Caeser what is Caeser's--financial and military support--who cares what race yu are or what god you worship.

ReplyDeleteMaybe America inherited some of that. But there has been a pretty clear WASP core ethnicity. The multi-ethnic empires of Persia, Akkad, and Gengis were monarchical, and Rome's republic was not extended beyond Italy; there it became an empire was full of puppet monarchies. America did inherit some pragmatic toleration of religious difference, but mainly from England, and mainly just toleration of different brands of Protestantism at first. I guess my point is that, at least from an historical perspective, there is a real tension between our liberalism and our republicanism.

Delete