Polanyi, decommodification, and the embedded economy.

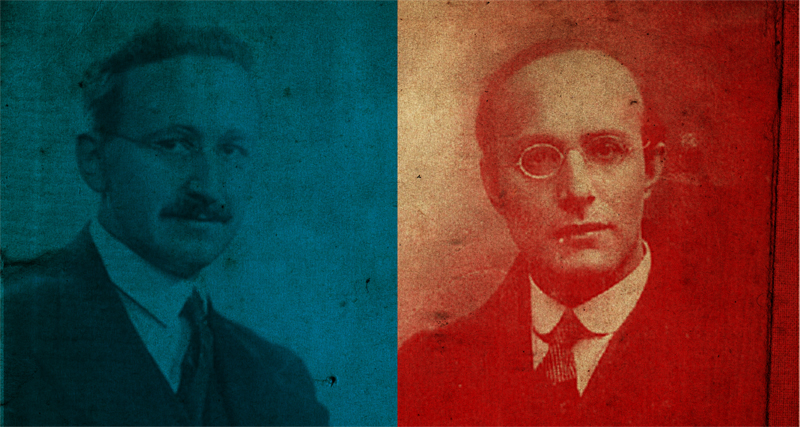

Karl Marx is certainly the most renowned critic of capitalism. His critique posited capitalism as the latest phase in the grand historical battle for the control of the production process. For Marx, the capitalist class had taken control of the means of production, just as the feudal nobility had controlled them before, and as the bureaucrats of ancient despotisms had controlled them before that. Karl Polanyi is not only a more obscure critic of capitalism, he is also often considered more moderate than Marx. He is associated more with European style social democracy than with revolutionary communism. And yet, if we look specifically at his critique of capitalism, it is arguably more radical than Marx's own.

Polanyi argued in The Great Transformation (1944) that when the "free market" becomes the governing model of economic life, this is not (pace Adam Smith) simply a modernization of our natural propensity to truck and barter, nor even (pace Marx) a penultimate step in the age old story of economic power politics, but rather a complete and unprecedented transformation of society. "It means no less" Polanyi wrote, "than the running of society as an adjunct to the market. Instead of economy being embedded in social relations, social relations are embedded in the economic system." (p60) This concept of embeddedness/dis-embeddeness is central to Polanyi's radical critique. As Polanyi goes on to assert, the dis-embedding of the market and re-embedding of society is a dislocation and a reversal so profound it cannot in fact be endured. "Our thesis," he writes, "is that the idea of a self-adjusting market implied a stark utopia. Such an institution could not exist for any length of time without annihilating the human and natural substance of society." (p3)

Polanyi's argument in The Great Transformation needs to be understood from its historical situation. The book was written at the close of WWII, and Polanyi believed that the early decades of the Twentieth Century--which saw the rise of fascism and communism, the abandonment of the gold standard, and the widespread embrace of market regulations following the Great Depression--marked the end of the grand experiment of a global market society, which had started in the early 19th century. Polanyi could not foresee in the 1940s that this starkly utopian experiment would be resurrected, zombie-like, in the late 1970s and early 80s, when Reagan, Thatcher, and others--under the influence of Friedrich Von Hayek and Milton Friedman--would again look to the unfettered market as a model not only for international commerce but for society itself.

What Polanyi did foresee, albeit in quite general terms, was the severity of the threat this revived economic order would pose to the global environment, or in his words, the "natural substance of society." His book, now 80 years old, is remarkable partly for its attention to environmental devastation, which he saw as baked into the capitalist order. Were the experiment allowed to continue, Polanyi said, the unregulated market as a de-facto social order "would have physically destroyed man and transformed his surroundings into a wilderness." (p3) He could not at that time point to the particular shape of the environmental crises that have since unfolded, such as the threat of runaway global warming, but his language of "destruction" and "annihilation," which could easily have been read as hyperbolic at the time of his writing, reflects quite accurately the existential nature of the threat that our globalized economic system now presents to our world. We face a radical problem, and Polanyi's radical critique provides a language adequate to articulate the ecological dislocation we are experiencing. His critique also give us concepts useful to us today as we seek a path forward, particularly the concepts of the embeddedness of the economy and the fictitious commodification of land, labor, and money.

The concept of embeddedness has also been central to a different and more recent critique of mainstream economics. Since the late 1970s, a small but growing coterie of ecologically astute economists began to issue the warning that infinite economic growth, on which capitalism as we know it vitally depends, is impossible on a finite planet. The central point made by the founders of what is now called "ecological economics" was that the human economy is (and must be understood to be) embedded in a larger system--the environment, the planetary ecosystem, Spaceship Earth, or call it what you will. Ecological economics asserts that we must somehow find our way to a steady-state economy that acknowledges this embeddedness and the ecological limits implied by it. From this starting point established by ecological economics, a few different movements and schools of thought have arisen. These break down most meaningfully along the question of whether the steady state economy can still in some way be a capitalist economy or must be an eco-socialist one.

While Polanyi articulated the severity of the generalized ecological threat, and while he argued at length for the embeddedness of economies in society, he did not theorize the embeddedness of societies within nature as explicitly as the ecological economists, nor did he articulate the specific problem of capitalism’s growth imperative running up against the material limits of a finite planet. What ecological economics adds to Polanyi’s critique is an articulation of the structural problem of limits to growth. What Polanyi can add to ecological economics is a sociological sophistication that the field too often lacks. Another thing he can add is a surprisingly moderate path to a solution which potentially defuses the debate between steady-staters and eco-socialists.

In Polanyi's analysis, the “great transformation” is effected by the emergence of three fictional commodities: land, labor, and capital. None of these is produced for sale, yet capitalism is based on trading each freely on the market. While Polanyi’s critique is radical, the remedy this theory implies is arguably a non-revolutionary one: selective decommodification. The pursuit of decommodification need not be an all or nothing endeavor. Many goods and services are already decommodified in many national economies. Free markets and entrepreneurship need not be annihilated. In fact they should not be. They must only be re-embedded in society, allowing society to become re-embedded in nature. Capitalism’s growth imperative can be defanged in a double sense: its scope can shrink considerably, and the economic dislocations resulting from periodic or systemic degrowth within the sectors left to the free market can be mitigated by a robust public sector.

Comments

Post a Comment