Mythbusting Climate Politics

My grandfather was an ecologist and among the early voices warning about the potential for global warming in the seventies and eighties. His influence was part of the reason I chose to study environmental science and politics after I graduated high school, in the mid nineties. I quickly realized that while environmental science is interesting and important, environmental politics is a bummer. Especially when it comes to global warming in the American political context.

My grandfather was an ecologist and among the early voices warning about the potential for global warming in the seventies and eighties. His influence was part of the reason I chose to study environmental science and politics after I graduated high school, in the mid nineties. I quickly realized that while environmental science is interesting and important, environmental politics is a bummer. Especially when it comes to global warming in the American political context.At the time it seemed to me, and I think to many other environmental-ists, that the situation is sort of like an irresistible force meeting an immoveable object. The irresistible force is the basic human need for energy which drives us to burn fossil fuels. It’s the easiest, most low-tech type of energy to access. And it is easy to conclude that humanity is simply destined to burn it all.

The immoveable object is the climate. It isn’t actually immoveable, unfortunately. But it is immoveable in the sense that changing it—increasing average global temperature by several degrees—very likely means catastrophe. That this catastrophe is all but inevitable has been a fairly common assumption among environmentalists for the last several decades. It is depressing, literally. There have been increasing reports of professionally induced clinical depression among climate scientists.

But there is hope, and here is why. The gloomy environmental outlook of the 20th century was based on two assumptions. The first is that you cannot have a healthy economy without fossil fuels. The second is that, because of the economic pain entailed in curtailing carbon, it will be impossible in a democracy to generate the political will to address global warming.

It has become increasingly clear to those who study this issue, however, that these pessimistic assumptions are no longer valid. One reason is that, in mature economies like ours, prosperity is becoming less and less dependent on economic growth. But even aside from that emerging trend, the use of fossil fuel energy is also becoming less and less necessary for economic growth. (Environmental economists call this “decoupling.”) For these reasons, the prevailing wisdom that curbing fossil fuel use means economic pain— for citizen-consumers and for nationstates— will soon be seen as outdated thinking. The question is whether it will be too late.

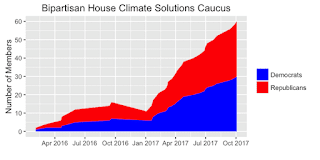

It may not be. The rest of the world is getting on board, and in spite of the the president’s recent withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, politicians on both sides of the aisle are beginning to recognize these economic realities. The political will to address climate change is no longer out of reach. The bipartisan Climate Solutions Caucus in the House of Representatives now has over 30 republican members, and it continues to grow.

One policy solution that is gaining bipartisan support is “carbon fee and dividend.” This policy would require corporations that import or mine fossil fuels to pay a tax based on the fuel’s carbon emissions when burned. The tax increases every few years. The tax money is not kept by the government, but given directly back to every American household in a monthly or quarterly dividend check. This dividend offsets the higher prices consumer must pay for energy.

The effect is to strongly and quickly incentivize the development and use of alternative energy sources, as well as energy efficiency, without hurting the economy.

Independent economic studies show that a carbon fee and dividend policy will not slow economic growth; it will create jobs and will actually benefit the average low-income American household. Similar policies are being implemented with success in other countries. Even some big energy companies support this. This is a policy that should, and truly can find support in both political parties together in the near future. The environmentalists of my grandfather’s generation would be pleasantly surprised.

Many Republican politicians, like our North Carolina Senators, Thom Tillis and Richard Burr, and our local representatives Mark Meadows and Patrick McHenry, do understand the global warming issue. And along with their colleagues, they are quickly coming to understand that realistic solutions are within our grasp. But too often politicians follow public opinion when they could help lead it in the right direction. Now is the time to write or call your representatives and your favored candidates, whether they are Republicans or Democrats, and urge them to address this issue.

Comments

Post a Comment